I’m a bit worried about this column. Not just this column, as a matter of fact, I’m a bit worried about most of the story columns you read, full stop.

I’m not worried about the quality; the writers and publications who produce columns and features about story are great (and I’ll get better… so there’s that). I’m certainly not worried about the prevalence; story columns get more column inches and kilobytes of data than columns on graphics, sound and level design, combined.

What I’m worried about more than anything, is the tone. I’m worried that the general tone of story columns and articles is largely negative, particularly when compared to other facets of games analysis. It is as if the journalistic body has collectively stamped game narrative with the words “MUST TRY HARDER”. I even fell into the trap a fortnight ago.

Whilst criticism in any medium is important, and often justified, when it comes to game narrative I think that we should all remember two substantial caveats. The first is that it is important to strive to be positive and, with so many great game stories available for players, currently the tone of the coverage doesn’t match the quality of the content. Secondly, if we are going to split games apart and analyse them piece by piece, we have to be really careful of the prism through which we analyse each segment.

I believe that the prism we are viewing game narrative through is often distorting what we see. Games, being the young entertainment-medium/art-form/who-cares that they are, slot into a much larger continuum of popular culture and entertainment which dates back through film to pictures via theatre, books and music. Like all that went before it, games have aspects which make them unique. Principle of these is the fact that games are driven, at their heart, by technology. Therefore, when we judge a game we compare it to two things: its peers and the past. Take visuals, for example. A game looks good currently if it compares well to other, similar, games released at the same time. Whereas, when modern games are judged against older games, the comparison centres around art style, because there is no way the older title can compete. We are aware, almost subconsciously at this point, that current games represent the pinnacle of the medium, the best that technology can achieve. You can debate the merits of art style all you like, but plug an N64 into a 46” TV and play Rogue Squadron through an old RF cable and you will see exactly what I mean. Graphics are the most obvious example, but you can apply the same logic to audio (the jump from chip-tune bleeps to full Dolby 5.1 surround might be even more stark than the graphical example), to A.I. and to the amount of content that can be squeezed onto a BluRay relative to a DVD or cartridge. My point is this; current video games are compared against their peers and their history, which means that the very best graphics, gameplay, audio and the rest, are rightfully lauded as the best the medium has yet achieved.

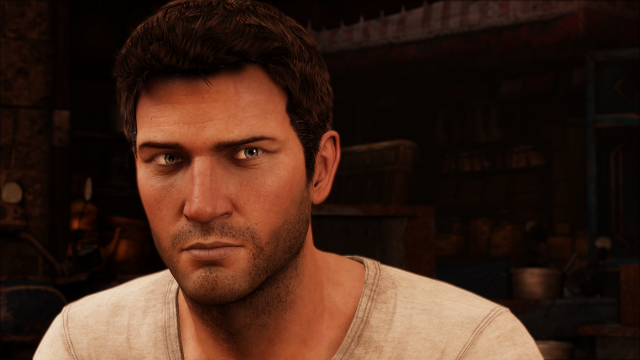

However, this is true for every aspect of games, except story. Stories that are the pinnacle of video game storytelling – Bioshock, Heavy Rain, Uncharted – are compared to the best stories across all media, including film-making (particularly), but also novels and television. We compare graphics over a thirty year period, but compare story over a thousand years. It is distorted analysis, judging story in a harsher light than any other aspect of games and against other mediums which have a quite a substantial head start in the story department. To properly understand how good video game stories are, we must change the way we look at those stories.

That starts with assessing the impact of history, and the march of technology, on game story.

When technology pushes forward the benefits to visuals and level intricacy are obvious. For those same advances, the benefits to story are less so. However, that doesn’t make the story we currently have in games bad. It is just that we have to stop comparing, subconsciously or not, game stories with every other type of story. Stories in games are new, arguably newer than graphics and level design and A.I. True stories in the early days of games were rare, with games like Zelda: Link’s Awakening being the exception, not the rule. Visual storytelling, the like of which we take for granted now, didn’t really exist until the 32-bit era. Video game stories are twenty years old. When movies were twenty years old they were silent. Think how far video game stories have come in the same time.

Advances in technology allowed films to have dialogue and music, changing them forever. Changes in video game technology have the same capacity. New discs and hard drives have massively increased the amount of dialogue that a developer can record. This gives studios the opportunity to create games like Mass Effect and have them come to consoles. Speaking of Mass Effect, compare the quality of the voice acting and the visual performance of the characters with a game like Resident Evil 2. A premier horror game at the time; tense, with a tight plot that held the action together. Acted out like this. This might seem like a snarky and unfair comparison, but it illustrates the progress that games have made in the last fifteen years. Yes, if you compare the emotional impact of a game story to a premier Hollywood film, the game will often come out worse, but that is an equally brutal comparison. Films are over one hundred years old! As time and technology move forward, things are only going to get better for games.

Even more exciting than what technology offers, is that the desire to tell great stories is evident amongst most of the world’s top studios. A few weeks ago I wrote about the potential of Borderlands 2 to deliver a great story, in no small part because that is what the developers wanted to deliver. They have delivered. The game has a sense of humour (call it wacky, call it rude, call it puerile, it is funny). The game has some tremendous dialogue, brilliantly delivered. In Handsome Jack they have a villain who is present, devious and painfully aggravating. The world is busier, with more interesting characters to talk to. From minute-one the plot twists and turns, trusted allies betray you and unlikely bonds are made. Pandora has always been an interesting world to be in and now what happens to the player in Pandora is equally interesting. The progress in design and delivery of narrative is obvious. It is a sign that Gearbox wanted to be better storytellers. Now they are. They aren’t the only example. Ken Levine’s team are trying to deliver something truly special in Bioshock: Infinite, providing the player with an A.I. character that they form a genuine bond with. Tomb Raider has decided to tackle a challenging issue. Gears of War: Judgement has brought in a writer who worked on Avatar to improve the narrative of a game that was already a huge success. Talent like Jeffrey Yohalem, a former employee of The Daily Show, has been brought in to make story front and centre in Far Cry 3.

This isn’t called the ‘Golden Age of Gaming’ for no reason. There has never been more choice of great games. Every aspect of games is going to keep improving because technology keeps creating opportunities and brilliant developers keep grabbing those opportunities.

However, we shouldn’t forget where we have come from, and that what we have now is the pinnacle of what the best game designers in the world can achieve. Those achievements include story. We shouldn’t forget that and writers should write about that.

I’ll try not to forget that, don’t you worry about it.