26th February 2019

At a certain point during your playthrough of Paradox Interactive’s Stellaris: Console Edition, a terrifying force will lay claim to your galaxy, enslaving its races, hoarding its resources, and carving a path of chaos and fear that turns stars black and reshapes the heavens. If you’ve played it right up to that point, that terrifying force will be you.

Not that the primary goal of Stellaris is total galactic dominion, of course; in fact, its just one possible victory condition. Although, I’ll be dead honest with you: it’s also the most fun you’ll have with Paradox’s complex strategy game.

Things start slowly and calmly, as you’d expect blossoming galactic empires would. Upon starting a new game you can select from a pre-made species or create your own, and immediately you’re presented with stacks and stacks of choice and personalisation. This is a Trekkie’s paradise, or a Star Wars fan’s, or Dr Who or Battlestar Galactic a or… Forget it, it’s just too inclusive. Let’s just say if you like the concept of communicating with deep and complex alien civilisations, this is your shit, right here.

You choose everything if you decide to start afresh. Species archetype first, where you decide if you’re humanoid, mammalian, avian, fungoid, reptilian, anthropod. Then you pick an overall appearance, a leader, a homeworld and local system. For most games, that’s enough, we’re done, give me something to shoot at. Not Stellaris. Now you’ll choose names, titles, racial traits, government ethics, political edicts, religions, aspirations, temperament, everything down to the flag and what the effing spaceships look like when you zoom in.

As the game opens, an in-depth tutorial is on-hand for those of you like me who A) have never played Stellaris, and B) usually only play games where you’re required to explode stuff with other stuff and maybe solve a block puzzle or two. And you will need the tutorial. I was 8 hours when I learned there was a tab to redesign my Fleet. It was 10 hours before I learned how to combine individual units, and another 2 before I even had to shoot at anything.

Because while war is the most engaging and exciting aspect of Stellaris, it’s only a small element for much of a given career. The bulk of your time in the early game will be spent governing, micromanaging and trying to prosper. There are close to a dozen different resources to manage, and the bigger your empire gets, the faster it’ll eat through them. To simplify matters, things like research are treated the same as minerals, power and food, so to keep your research high enough you’ll need to build stations orbiting interesting planets in the same way you need mining stations in the orbit of mineral-rich planetoids.

At first it’s daunting, but before long you’ll find a steady rhythm in the gathering and spending, your little world will thrive, you’ll assign scientists and governors and send science ships out to seek out new worlds. And it’s at precisely this moment of relative comfort that Stellaris will drip-feed you the next set of instructions and ask that you expand your empire to the nearest habitable planet. There’s an almost indefinable thrill to that first expansion, a sense of accomplishment unattached to trophies (which, oddly, Stellaris doesn’t support unless you’re in the single save Iron Man mode). You construct a colony ship, name your new world, install a government, and start again, all the while surveying distant star systems and constructing frontier outposts on the edge of known space.

It’s at this point, when you’ve developed more efficient spaceports, established a new colony and begun to really pay attention to the politics of your worlds (your peoples will elect new governments, create new factions, and preside over edicts without your direct control), that you’ll usually attract the attention of another intelligent species. Some of this you’ll control, as you pick the size and shape of your galaxy, and the number of potential empires within it when you begin a new game. Whether or not they’re friendly, advanced, superior to you, or impressed by your technology is all procedural each time, and if you have more than one empire on the go, you can opt to have your alternates show up in your current galaxy, which is very cool.

This period is really the meat of the game, as more and more alien races join the fray. Now you’ll suddenly worry about your distant colonies, assigning them to Sectors that mean they essentially become fully autonomous, reducing the need for micromanagement. You’ll construct military installations, fleets of attack ships, and recruit generals and admirals to lead your armies. Research projects become more defence oriented, and trade negotiations become integral. A healthy alliance is all well and good, but if two empires you’re allied with go to war, you may be forced to pick a side.

Choice is everything in Stellaris. So often I found myself just sitting back in my chair and watching my empire thrive, researching an extinct alien race here, uncovering a precursor civilisation there, maybe dabbling in a little politics or sending a science ship to the far side of the galaxy for funsies. Do you research better food production or better plasma cannons? Do you accept the raw end of a trade deal or throw down the gauntlet? All of a sudden, you’ll realise everything clicked a few hours ago and you didn’t notice, as you start remembering impossible-to-pronounce names, and rebranding your fleets, stations and ships becomes a priority. You might wage a war for the freedom of slaves, or defend an empire against a galactic bully. You might decide to be the bully yourself. Either way, you’ll slowly begin to tick up the victory percentage – which brings us rather neatly to the endgame. And what an endgame it is.

Enabling “Endgame Crisis” ensures that as you approach the final push towards your victory conditions, something momentous will occur to shake the foundations of the galaxy. Often these events change the entire feel of the game, forcing you to band together with former enemies, or wiping out allies altogether. It might be an invasion by an advanced species from another dimension, or a robot uprising that sees your empire crumble around you. They are an exceptional touch and ensure that you go out on a high, successful or not.

One thing that truly surprised me was the control scheme. Something so dense and layered on a PC, especially something as regularly updated and consistently changeable as Stellaris, would usually be a total mess on console, with essential controls relegated to umpteen different dial menus and hidden behind intrusive tutorials that treat you like an idiot. Stellaris’ control scheme is incredibly intuitive. Left on the D-pad is your primary menu, a list of icons that give you instant access to your empire’s backstage, from ship design and personnel to research menus and political control. Up jumps to the resource bar where you can glean easy-to-understand information about your current stockpiles. Right opens the Outliner, a list of every world, ship, fleet, faction, and rally point in your empire. Finally hitting down will access the notification bar, where you can respond to any development, from the death of a general to the completion of a research project. And you can either follow your Situations Log for hints and direction, or ignore and do whatever the hell you want.

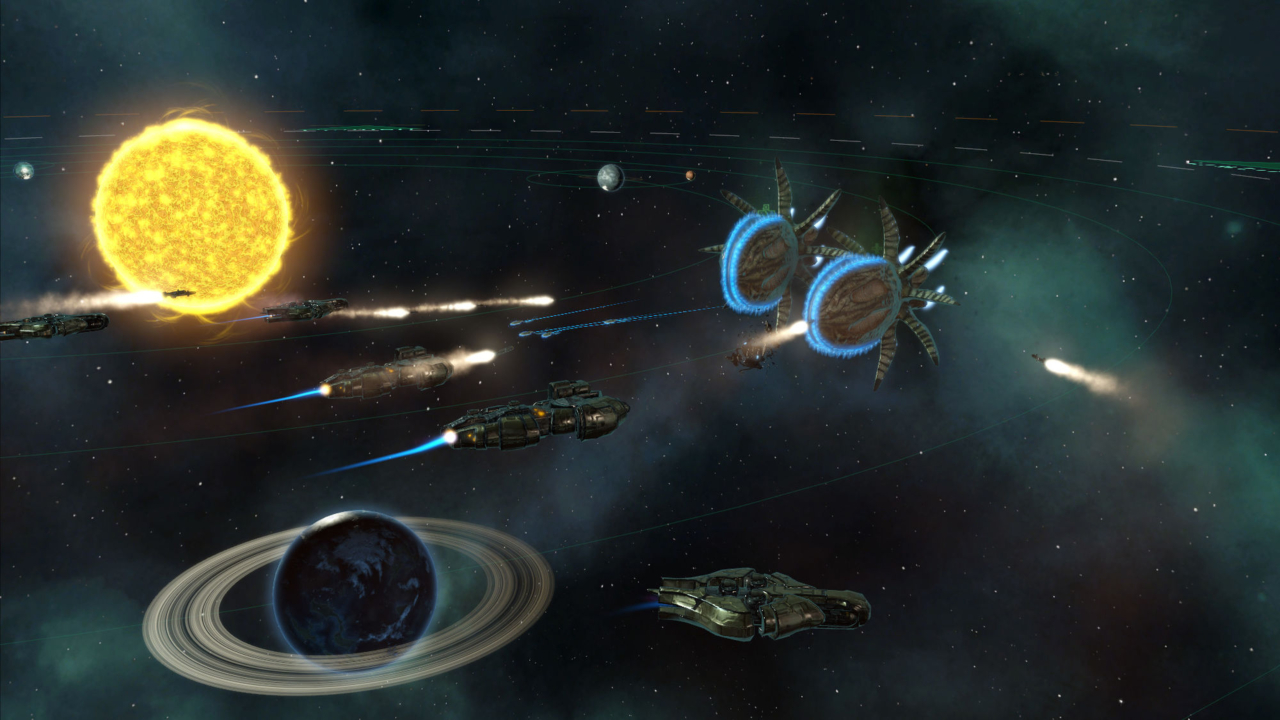

There are deeper options within options, too. The ability to adopt or outlaw slavery, the option to build robots to serve you, the choice between pushing for education reforms and the construction of religious sites, or increasing your naval strength and training ground troops. One thing Stellaris always manages to maintain is the feeling that you are in the front seat of an epic adventure, as you zoom in to watch a space station being constructed, or put yourself in the heart of a pitched battle as laser beams cut the night and ships pop in blooms of oxygen-starved flame. The textures are often fairly simplistic when zoomed out, but up close the planets, stars and ships pop with colour and life, and while it’s not always utterly arresting, it does a good job of maintaining its atmosphere.

Stellaris is a difficult game to criticise, particularly on console because there is so little like it. Nothing I can conjure in memory comes close to this level of grand strategy outside of the PC. Is it dense? Incredibly. Too dense? Maybe, actually. It lacks instant gratification, instead demanding an investment of time and patience and, Christ, so much reading and listening. For PC gamers raised on a diet of menus and micromanaged civilisations, perhaps much less so, but for a simple bombast fan like myself? You betcha. It’s also hard to really judge the difficulty, as I found that even with only a few AI empires and the aggression set to Low, I was getting my arse handed to me by overly sarcastic squid-monsters and prissy birdmen on regular occasions.

But hey, I went into Stellaris with no prior knowledge of the IP and the complete expectation that I would come out 10 hours later utterly bemused, but here I am pushing past hour 25, on my third and most successful empire to date, secure in the knowledge that there is still hundreds so much I haven’t even seen yet. It’s a beautiful, busy space adventure that rewards you as much for careful, considered strategy as it does for building a 40-ship fleet as early as possible and going ham on anything with more than one pair of eyes. You might be tempted to overlook Stellaris right now with so many big games crashing onto console, but if you’ve even a passing interest in epic sci-fi and armchair strategy, this is well worth your time.

So many options

Looks gorgeous at times

Endgame crises are incredible

Very dense

Starts slowly

AI difficulty can feel inconsistent

Stellaris is a beautiful, busy space adventure that rewards you as much for careful, considered strategy as it does for building a 40-ship fleet as early as possible and going ham on anything with more than one pair of eyes.