What Remains of Edith Finch is a collection of short stories about the deaths of a family, tethered together by the last remaining member of the Finch family as she explores her old family home in search of answers. It’s a profound game, full of powerful retellings of the final moments of life, and it’s connection to our own experiences with loss and grief. I was fortunate enough to speak to the game’s Creative Director, Ian Dallas, about many different things, including the way it grew from a scuba diving simulator, how the bedrooms were created, dealing with death across different ages and portraying it in a way that understands player fragility, and the ways in which Giant Sparrow uses text as part of the environments.

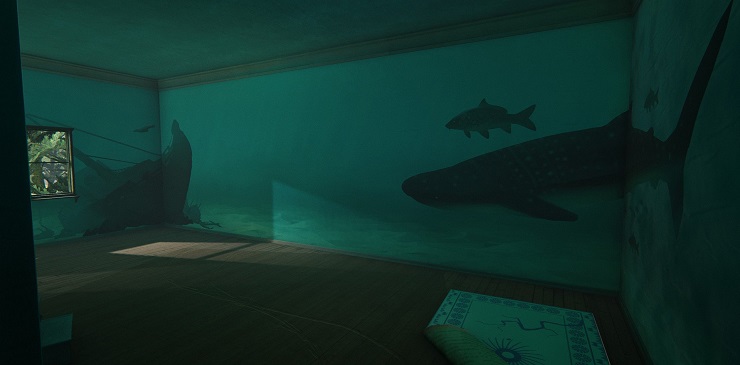

So where did the idea come from, and was it a decision early on to deal with loss, and the impact of grief? “It wasn’t where we started from, but the initial seed was trying to explore what it was to experience the sublime, which is simultaneously beautiful and unsettling. That’s the little seed that everything grew out of. We started off making prototypes of spaces or experiences that felt like they would evoke those feelings. Personally, for me growing up in Washington State, one of the key memories I had was being at the bottom of the ocean and looking at the ground as it sloped away into infinite darkness. And just feeling small and fragile, but in awe of how beautiful everything was and just feeling connected to that.”

“We started making a scuba diving simulator, which was the initial version of this game. I think we quickly realised that that was interesting for about 10 mins or so, but knew it couldn’t be a full game. So we started looking at other references and works of art that had explored similar kinds of feelings, and came across weird fiction. Authors like H.P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allen Poe and Neil Gaiman – they were a wide range of writers who were all concerned with a universe far bigger than you could possibly imagine.”

“We wanted to focus less on the universe, and more on the experience of individuals within that universe. To put the player in that mind-set of a person experiencing those awe inspiring moments. We knew emotionally where we wanted these stories to land and to find the best way to build that concept.”

It was really interesting to find out exactly how they wanted these stories to impact the player, and just how they built the individual bedroom scenes. “In terms of creating these bedrooms and the moment of hand off between Edith and these stories, if we were going to give players these really emotionally experiences we needed to ease them into it, and then ease them out of it, providing them a period of relative calm. At any given time you can only really take in so much, and this game is all about being overwhelmed, so in each of the stories the characters are being overwhelmed, but so are the players – how are we moving the characters around, what are we doing and what’s going to happen etc.”

“Then by the end of it hopefully it’s something that takes your breath away, and then you need a bit of time to pause. Viewers don’t give themselves time to pause these days – people have been so conditioned to give themselves goals, and getting antsy and frustrated, and angry. So we tried to give them calm, with a brute force approach where we force you to look at the family tree. That was a way to kill a lot of birds with one stone – who this person was and there role within the family. We wanted to force players to take a breath, and also give Edith time to breathe.”

One of the most powerful stories told in What Remains of Edith Finish was Gregory’s. How do you even tackle the death of a baby, and at the same time do it so successfully, tactfully, and beautifully? It was interesting to hear just how Ian and the team approached it. “I think that was a result of making a bunch of other stories and feeling out where those stories worked. What we realised eventually, the canonically Finchian moment was putting players into a place where they knew what was about to happen, but there’s a joyful inevitability to it. What you’re doing in this moment is playful and interesting and you also have a sense of curiosity to be excited about it, marching happily to your doom. That combination of bittersweet inevitability, but also joy, where a lot of that is the music and the art.”

“Gregory’s story went through a lot of different versions. In one it ended with the water rising, but that seemed like too much of a gut punch. I think having the moment of going under water and having control gives you forward momentum of going on a journey as opposed to ending with a curtain rising in front of you. It was also very interesting because we were working on isolated prototypes and we had people come in and play them for 5 or 10 minutes, and after 2 years we had a few stories linked together. Gregory’s story worked better after playing a few others before it. When it’s a baby and you know it’s going to die, there’s already an innate heaviness, so we stripped back everything we could to try and make it a bit lighter, because the players bring their own heaviness to it – we don’t need to add to it. When our game play programmer threw in Waltz of the Flowers it was the perfect piece of music – I think we were struggling with the darkness on that one.”

If you’ve played The Unfinished Swan, you know Giant Sparrow has a fondness for using words – or text, within the design of the environment. I’d always wondered why, and with Edith Finch, it’s even more prominent, but was it a design choice, or did it come a long naturally? “I think it’s a little bit of both. Initially we were looking at as a way to foreground the idea you were reading a story. You’re conscious you’re not getting a factual account, but an emotional telling of what this person choses to remember, and the words inside the world was a way to visually call that out. Once we had that as a functional element, it was a way to solve a lot of other problems, like indicating where players had to go, what might be interesting in a room, and also provide visual feedback.”

“Once you strip away a lot of traditional game elements, like green arrows and mini maps, you end up with a world that’s a bit sterile. We didn’t want a world that was cold, and the text was a way to warm things up a bit. Also, as a designer I’m interested in typography and the visual styling of text, and it was exciting to give each of these stories a different typeface to echo who each of these characters was.”

There are a lot of moving parts in this game, such as the various short stories, intricate detail in the house design, amongst other things. I wondered just how difficult it was to bring it all together. “It was not easy. The way we tend to work is we start with something concrete and build out from there. We’re going out into uncharted territory. With the story, overall, we began with more of a focus on the short stories; they were already fully formed where we could give them to a programmer where they could add to the story and the process.”

“At various stages we had about 5 stories where we would be writing a script for one, recording voiceovers for another, building environments for another. There was a lot of a really nice crossover, where there was a lot of power with having the same stories take place in the same location. For example, the swing set. When you walk up to the house and you can see in Calvin and Molly’s story different perspectives through time. In some ways the story tells itself.”

It’s such an emotional story for the player, but what impact does it have for somebody who’s been working on developing the game for a long time, and do the characters’ stories still feel poignant? “After two or three years, no (laughs). I feel more connected to the characters when they didn’t exist because I’m trying to imagine who they might be. There’s only so long you can look at these things to feel like you’re seeing them for the first time.”

Like all great developers, Ian Dallas of course keeps his ketchup in the correct place. “Hmm, I do keep it in the fridge, but growing up, I remember we kept it in the cupboard. I guess the Finches keep it out – I’m not sure who made that call. As the creative director, I don’t think I was consulted.”