The GodisaGeek Retro Corner: Blade Runner

Developer: Westwood Studios

Publisher: Virgin Interactive Entertainment

Originally Released on: Windows PC

Currently Available on: Currently Unavailable

Video games which have been adapted from films are notorious for being rush-jobs or ill-conceived spin-offs. All too often, the game sticks so closely to the plot of the film that there are no surprises for the gamer and the story is squeezed into a game engine that can’t possibly handle it. Either that, or the title relates to the film so little that it is barely recognisable as being part of the franchise.

With this in mind, few would have thought that one of the best film adaptations in recent memory would be a branching adventure game developed by Westwood Studios, a studio famous for producing real-time strategy titles such as Dune II and Command & Conquer.

Before they closed in 2003 (after being purchased by Electronic Arts in 1998), Westwood almost single-handedly created the real-time strategy genre before proceeding to make it one of the most popular types of game on the PC. But once the demands of EA were placed over their heads, their games became rushed and unfinished, meaning that consumers lost faith in the once-strong Command & Conquer brand.

After Westwood’s collapse, few remembered that the studio also had a flair for adventure games. Before the 1997 release of Blade Runner, Westwood had produced a trilogy of adventure games that made up the Legend of Kyrandia series. Critically acclaimed, but perhaps never obtaining the retail success they deserved, these titles have somewhat faded into obscurity.

But thanks to the cult following that surrounds the Blade Runner film, the game adaptation has continued to benefit from an enduring affection. Remembered fondly by those who played it but unknown to those who didn’t, the game is certainly one that deserves the digital download treatment.

But thanks to the cult following that surrounds the Blade Runner film, the game adaptation has continued to benefit from an enduring affection. Remembered fondly by those who played it but unknown to those who didn’t, the game is certainly one that deserves the digital download treatment.

For its time, the game was a revolution in branching, open-ended gameplay. Further to this, the ingenious use of Voxel technology meant that the game could use 3D models without the need for gamers to buy a PC with graphics accelerators. So let us delve a little further into what made this game so intriguing and how it helped to re-invigorate a 15 year-old movie.

Rather than follow the well-travelled road laid down by Ridley Scott’s film, Westwood instead worked in tandem with writers who worked on it to create a new story that runs alongside the film’s events. The game’s story begins shortly after that of the film, and sees players take control of Ray McCoy, a Blade Runner whose job it is to police unauthorised and dangerous Replicants (androids who look, act and think almost exactly like humans) on Earth.

As McCoy, you are set on the trail of a group of these rogue Nexus 6 Replicants who have come to earth whilst the movie protagonist Deckard pursues another group at the same time. The two story lines overlap somewhat in terms of shared locations and characters, and Westwood even throw in a few well-hidden easter eggs and references to the film that fans will enjoy looking for.

By following a new story, the developers could open up a whole new batch of possibilities for exploration in an already established and well-loved world. Technology from the film is accurately implemented into the game. The most notable example of this is the Voight-Kampff retina scanning machine, a device which measures the responses of an interviewee to ascertain whether they are human or android.

By following a new story, the developers could open up a whole new batch of possibilities for exploration in an already established and well-loved world. Technology from the film is accurately implemented into the game. The most notable example of this is the Voight-Kampff retina scanning machine, a device which measures the responses of an interviewee to ascertain whether they are human or android.

Like a lie detector test, the player must use this machine to judge a subject’s reaction to emotionally-charged questions. Carry this out correctly and you can identify a replicant before they get the chance to kill you. Judge badly however, and you might condemn an innocent citizen.

There is also the Esper evidence scanner, which has many functions including the ability to enhance photographs in order to reveal previously unseen clues. These machines prove invaluable in your investigations, and the fact that players use exactly the same methods that Harrison Ford did in the film really helps ratchet up the feeling of being immersed in the same world as the movie.

The graphical representation of that same world both impresses and repulses in different ways. The game has aged particularly badly when it comes to character models. Released at a time when graphic accelerator cards were not terribly commonplace, Westwood Studios didn’t want to create a game that relied on 3D models. Instead, they worked on a new system called “Voxels Plus”, which makes use of voxel technology, which works with three-dimensional pixels rather than full 3D wireframes to create models .

The graphical representation of that same world both impresses and repulses in different ways. The game has aged particularly badly when it comes to character models. Released at a time when graphic accelerator cards were not terribly commonplace, Westwood Studios didn’t want to create a game that relied on 3D models. Instead, they worked on a new system called “Voxels Plus”, which makes use of voxel technology, which works with three-dimensional pixels rather than full 3D wireframes to create models .

This meant that even a computer without a graphics card could run the game, but because pixels are generated by the computer processor, only really fast processors could handle high voxel usage. This resulted in the development team having to use a low pixel count in their models, which means that the characters look very pixelated, especially close up, because the pixels don’t scale at all.

On the other hand, the environment art, lighting and ambient effects are exceptional. The backgrounds are all fully pre-rendered with some incidental animation. Admittedly, this does jar with the voxel character art, but it does accurately represent the locations seen in the film.

On the other hand, the environment art, lighting and ambient effects are exceptional. The backgrounds are all fully pre-rendered with some incidental animation. Admittedly, this does jar with the voxel character art, but it does accurately represent the locations seen in the film.

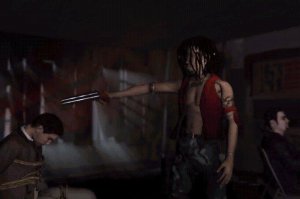

Those locations are instantly recognisable, and along with the lighting, players can experience the atmosphere of a seemingly forever dark, neon-lit city, crawling with criminals and dodgy-looking areas. Rain and shadow effects further enhance the feeling of unease, and Westwood really play on the idea that your enemies could be lurking in any dark corner, making the player feel like no location is truly safe.

Sound design too is very faithful to the film. The original score could not be licensed, but a new composer was brought in to re-record the famous score and add in extra pieces of music which would adhere to the established Vangelis style. The music is always atmospheric and evocative of the futuristic city, adding to the drama and suspense experienced during gameplay. Sound effects are true to the film and voice acting is generally superb, featuring some of the actors from the film reprising their roles in cameos. New voice artists also fit in well and are perfectly suited to a gritty sci-fi thriller.

Gameplay-wise, the title is a point-and-click adventure game at heart. Action situations are added where quick reflexes with the crosshairs will be required, but the majority of play consists of mouse-based investigation of scenes and conversing with non-playable characters. Conversation sequences allow players to choose the stance McCoy will take, be it passive, aggressive or comedic. This affects what responses you give to people and how others react to what you may say.

Gameplay-wise, the title is a point-and-click adventure game at heart. Action situations are added where quick reflexes with the crosshairs will be required, but the majority of play consists of mouse-based investigation of scenes and conversing with non-playable characters. Conversation sequences allow players to choose the stance McCoy will take, be it passive, aggressive or comedic. This affects what responses you give to people and how others react to what you may say.

That said, unlike other adventure games, there aren’t the regular inventory and conversation trees you might expect. Instead, you acquire evidence which will be logged and kept for further examination. All of the responses and pieces of evidence you collect are compiled in your Knowledge Integration System, which is an automated way of pulling facts together.

Unearth enough leads and clues, and the story starts to piece itself together. Examine evidence further using the Esper, and you open more leads that add weight to your case and help confirm your suspicions. This does mean that if you play the game carefully and explore all leads, you will get a very clear picture of what is going on. Decide to be gung-ho and shoot up the place however, and the story will soon pass you by.

All of these tasks are handled with a simple mouse pointer. Unfortunately, this means that if you click the relevant button, McCoy will draw his gun, anywhere! This can be used to scare suspects or chase someone down, but drawing your gun at the wrong time can result in a sticky end for the player. The reverse is also true, because if you don’t draw the gun quickly enough when you need to, you won’t have time to deal with your enemies.

All of these tasks are handled with a simple mouse pointer. Unfortunately, this means that if you click the relevant button, McCoy will draw his gun, anywhere! This can be used to scare suspects or chase someone down, but drawing your gun at the wrong time can result in a sticky end for the player. The reverse is also true, because if you don’t draw the gun quickly enough when you need to, you won’t have time to deal with your enemies.

All too often, you will enter a new scene only to be gunned down before you realise what is going on. Players are forced into a kind of trial-and-error in these situations, as they must learn when they need to be quick on the trigger. That said, being able to draw the gun at any time does add a dimension of freedom to the game. You can shoot suspects more or less when you want. You could try to test a possible Replicant with the Voight-Kampff machine to make sure, but they may run away scared and then what do you do? Blade Runner gives you to option to chase them down, let them go free, or “retire” them.

This is where the real key to Blade Runner lies; there is a lot of freedom within the game. Having twelve different endings isn’t a gimmick because these conclusions can be reached in very different ways. A player could go through the game several times, achieving multiple different endings and yet they might never reach some of the most important locations in the game.

These aren’t just simple cheap endings where McCoy dies early, these are unique conclusions where the whole story has played out but to a different end point. Kill a particular character and whilst you may be commended, you will never reach another vital clue. Add to this the fact that every time the game starts, there is a degree of random generation, whereby characters will appear at different locations or at a different point in the story, and you have a game that seems to be always changing.

Whilst these changes won’t seem to influence play greatly at first, each decision leads the player towards a different outcome. The endings are varied, including a neutral one, one where McCoy kills Replicants or even one where he appears to be a Replicant himself.

These little story tweaks make the user feel like they are the director of the Blade Runner film. Play as the hard-boiled cop and you may constantly finds yourself in fire-fights without any choice in the matter. Play more conservatively and a more contemplative approach will open up.

These little story tweaks make the user feel like they are the director of the Blade Runner film. Play as the hard-boiled cop and you may constantly finds yourself in fire-fights without any choice in the matter. Play more conservatively and a more contemplative approach will open up.

The release of Blade Runner saw a true multi-path game emerge at a time when few considered it a viable option. Your morality will be put to the test and the outcome depends entirely on how the player interprets both the actions of the characters in the game-world and the personality of their own character. This is both a gift and a curse because there are certain characters I could never bring myself to kill, so I couldn’t experience every possibility.

And this is what makes the game a morality stick. It asks the question “how would you act if you found yourself in the world of Blade Runner?”. Knowing that every path you take changes the story according to your own personality makes it an experience unlike most games.

Blade Runner is currently not available for purchase via retail, nor on any retro gaming download services. It can be bought second-hand, via services such as the Amazon Marketplace. The God is a Geek Retro Corner will return on the first friday of next month.