Story is important to me.

Not necessarily narrative, or even plot, but there has to be something in the background of a game to give what I’m doing some kind of context. Even Space Invaders – even Pong! – have a very basic story, if you look at them from a certain angle. And, of course, there’s always the imagination, the poly-filler that can fabricate a plot out of just about anything, no matter how simple the base concept may be. Pong! would almost certainly require more imagination than Space Invaders if you really wanted to give your little paddle a backstory, but it’s possible.

These days, it’s left almost exclusively to the indie scene to produce games that are just, well, games – and while popular hits like Super Meat Boy and Spelunky don’t need a story, they do have context, in that they give you a reason to do what they want you to do that corresponds to their specific universe.

More and more triple-A’s these days are “story-driven”. Take recent hits like Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us. The mechanics in either game aren’t particularly exciting in of themselves. The Last of Us basically borrows almost its entire repertoire from Tomb Raider and Uncharted, while Bioshock Infinite is a fairly pedestrian first person shooter. However, the impact of their narratives, the palpable affect they have on the gamer, elevates them far, far beyond the mundane. Similarly, without the story, Heavy Rain is just a very long series of single button presses and stick-waggling. For those games, story isn’t just important, it’s essential. Absolutely vital.

On the flipside of the mainstream coin, you have Left 4 Dead, a game that presents a framework within which a zombie apocalypse makes sense and then sets you free to play through the “story” In any way you choose. Or you might site Dark Souls, which creates a world, a challenge, and lets you fill in the details yourself while you attempt to avoid an unceremonious end. Story is important to create context here, but the gameplay carries itself.

As developers of AAA titles strive more and more to create a “blockbuster experience”, story, setting and context become more important. And stories grow, like planted seeds, into multi-branching oaks, aided by the Extended Universe, often little more than a machine built from cheap parts to make lots of money. Every other big game now has to have spin-off novels that, generally speaking, don’t need to be particularly well-written to shift units. There are decent examples, like The Fall of Reach, Eric Nylund’s epic prequel to Bungie’s Halo, or James Swallow’s above-average Deus Ex: Human Revolution tie-in, Icarus Effect. But some of these companion novels are truly terrible.

William Deitz’s Mass Effect novel, Deception, was so bad it incited a torrent of internet hate when fans discovered the huge liberties taken with the universe and characters, and the ridiculous number of perceived errors. He might have argued that it was artistic license (after all, film directors get away with it all the time), but we gamers are passionate if nothing else, and that shit just don’t fly. The Mass Effect novel is an extreme example, though, and quite often it’s a case of low quality rather than incorrect content; tie-in novels rarely truly evoke the same sense of scale and wonder as their videogame counterparts.

What often works far better is the same thing approached from the opposite direction. Games based on books tend to have a focus often missing from other big releases. Take The Witcher games by CDProjektRED, or the Metro series. For me, personally, the storylines on offer are exceptional, fully grounding the games within their respective universes – even to the point where the mechanics are shaped to fit the world, and not the other way around. The crossover between game and novel is front and centre – it’s neither a cynical cash-in or a half-arsed spin off. Games based on novels are made because someone believes it’s a worthy enterprise, because someone respects the source material, because someone is passionate enough to make it happen.

Story is important to me. Whether it’s a game based on a book, a book based on a game, an indie that puts gameplay first and foremost or a brand new IP hoping to challenge the current bestsellers. Arkane Studios’ Dishonored is an example of the latter. Here’s a game that made its setting the star of the show. The city of Dunwall, one-third Victorian London, one-third gang-land era New York, one-third steampunk fantasy, is almost a second protagonist beside masked murderer Corvo. You may remember that I kind of liked Dishonored when I reviewed it last year, and the story was one of the main reasons it resonated with me.

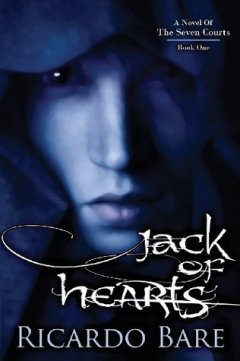

A lot of the appeal comes from how Dishonored was written, not just as a game, but as a narrative experience, an adventure set in a fully realised world, one whose history is documented throughout the game, revealed in intricately crafted journal entries and Easter Eggs. Dishonored’s Lead Designer, Ricardo Bare, is a man who understands the pressures and joys of working in both games and literature, having successfully segued from video games to novels with his recent release, Jack of Hearts.

For me, it’s not enough for a game to simply tell a story through shooting stuff, anymore than it’s satisfying to blow things up because I’m told to. I like a happy medium somewhere in between, where my actions matter, where they have an impact on the world I’m immersing myself in. As a games writer and a budding indie novelist myself, it’s fascinating to watch the story of a game unfold through my character’s eyes – and if that story is compelling enough to make me forget, even for a moment, that the events aren’t happening to me personally, then that game is a winner in my eyes.

Ricardo Bare was kind enough to take the time to speak with me recently and share some of his invaluable experience, to grant us a brief insight into how he came to write both video games and literature. When you’ve read the interview, please do check out his debut fantasy novel, Jack of Hearts.

Ricardo Bare was kind enough to take the time to speak with me recently and share some of his invaluable experience, to grant us a brief insight into how he came to write both video games and literature. When you’ve read the interview, please do check out his debut fantasy novel, Jack of Hearts.

Hi Ricardo. So, first of all, how did you get into writing for games?

I started out as a level designer, which I still do regularly. I was pretty fortunate, in fact. In college I was heavily into fiction and gaming and by then I’d begun to strategize about how I could somehow get into the gaming industry. I’d read an article on game design by Harvey Smith which I found intriguing (I think it was Distinct Function in Game Units), so I wrote him. He wrote me back, which blew me away. He gave me a bunch of advice, part of which was to look into this new game called “Unreal”, because it shipped with a level editor.

I spent every spare minute learning UnrealEd, until I had enough material to get me in the front door of Ion Storm, where I ended up working on Deus Ex. From there my work mostly entailed the kind of storytelling level designers do: environmental, dramatic pacing, arranging challenges, working closely with team writers to integrate dialogue and so on.

Coincidentally, if you’re into table-top gaming, this sort of work is very similar to the kind of storytelling a “dungeon master” does. It’s far less about prose and dialogue and more about crafting compelling or dramatic scenarios.

Since then my role has broadened to include more actual writing, such as story structure and dialogue, but I don’t carry the title of “writer” on the team. That title is for someone who does that 99% of the time, which I don’t. But my role overlaps heavily due to my interests, the kind of games we make at Arkane Studios and our team structure. In fact, the function of storytelling is spread out across many “job titles” at Arkane. Someone trying to come into the industry purely as a writer for games would likely have a much different path.

Did you ever have to deal with rejection? If so, any advice for those trying to break into the industry?

Did you ever have to deal with rejection? If so, any advice for those trying to break into the industry?

Persist. That’s the best thing you can do. I’m talking about writing in general, not for games here. I once read an anecdote about Stephen King. He kept every rejection slip and nailed them to the wall. I found that story encouraging, so I followed suit and kept all my rejection slips. I have a folder with dozens of “no thanks” letters from agents and editors, and that’s not counting the digital rejections I have in email!

It’s easy to get discouraged. I tried to think of every rejection is one step closer to getting published. My co-worker Raphael Colantonio calls these kinds of experiences “Near Successes” and I think that’s a great perspective. Most of the writers I know who strictly do writing for games either started out doing something else (game or level design) and transitioned, or they were already writers outside of the games industry.

What was it like going from writing games to writing a novel? Was it an easy switch?

I’ve almost always done both at the same time, but that’s very hard to do during the most intense part of a game’s development cycle. So I tend to follow a law of undulation. When the workload for a game isn’t as intense, I ramp up how much writing I do, and vice versa. Near the end of Dishonored, for instance, I did very little writing. Before that I wrote and revised the bulk of my novel, Jack of Hearts.

Which form of writing do you prefer?

That would depend on the day. Writing short stories and novels is often a sort of creative retreat for me where I can fully explore ideas on my own. One thing they have in common which I really enjoy is world-building: inventing characters, monsters, interesting locales, and so on. Lots of attention to detail.

On the other hand I really enjoy the excitement of collaborating with my teammates to bring something new to life. The character of Granny Rags from Dishonored is a good example of that. I owned that character’s thread through the game, but the final result was a big collaboration with many team members. She started as a kernel of an idea: a blind homeless lady who sat on a park bench each day to feed “pigeons” which turned out to actually be plague rats. Working with Harvey and Raf [Colantonio – Dishonored’s Creative Director], she morphed into something more sinister as we developed her connection to the Outsider and her weird lucid madness. The notion that she was a fallen aristocrat was eventually added, which the artists at Arkane nailed visually. Austin and Terri rounded out her character with more dialogue, and with Christophe Carrier and the other level designers we worked out the details of her story line.

Finally, add the amazing voice of Susan Sarandon and you have the Granny Rags that players meet at the end of Endoria Street. You give up a lot of control, but when you’re working with talented people that you trust you get something wonderful in return. And you grow as a creative person. Oh, and inside my head I’m doing this in all caps the whole time: “OMG!!! I TYPED SOME WITCHY WORDS THAT SUSAN SARANDON SAID OUT LOUD!!!”

What do you think of games based on novels? Can they ever be successful, or will they always disappoint because of the passion people have for games?

I think that largely depends on what people do with the concept. Taking advantage of the medium of games and including meaningful interactivity is probably critical.

Conversely, what do you think of the recent increase in games based on novels (The Witcher, Metro 2033)? Do you see this as a good thing, or an indication that developers are running out of ideas?

Not at all. I don’t think it means developers lack imagination. I think a more charitable perspective is that people have a great appreciation for a particular universe and would like to see it come to life in another medium. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

Also, I’m not sure if there’s been an increase lately, maybe only proportionally because the entire market is bigger. But I feel like we’ve always had a lot of games based on novels. I remember playing the text adventure Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the strategy game Dragonriders of Pern, or the RTS based on Dune among others.

I think you can do at least two things with games based on novels. You can say, here’s this really interesting universe and we’re going to let players explore this world in an interactive fashion. That’s all good and well. So, for instance, you could take Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun series and make a traditional RPG or adventure game with it. Maybe not too interesting in terms of game design, but I would still buy this instantly.

The second thing you can do is look at some of the concepts in a novel and try to derive game mechanics that embody those ideas in a meaningful way. In the game based on the Book of the New Sun for instance, maybe you could do something with unreliable narration, warping time, and eidetic memory. That, after all, is the strength of the medium.

How long were you working on Jack of Hearts – and will we see more in the series?

How long were you working on Jack of Hearts – and will we see more in the series?

I wrote the first draft of Jack of Hearts in a quick blast after Midway Games went bankrupt. I rode my bike to a nearby coffee shop and just pounded away on the laptop while I was unemployed. That took a few months. Then the hard part began. Editing and revising took well over a year after that, stretched out by lulls where I got busy with game development or distracted by other writing projects. During that time I also accumulated a pile of rejections from agents and editors, but I also learned a lot.

Now that Jack of Hearts is finally out – something which still feels utterly surreal to me – I’m right in the middle of writing the next book in the series. In fact, I should get back to that now!

Right you are. Before you go, where do you keep your ketchup – fridge or cupboard?

Fridge! Who likes lukewarm ketchup? All dried out and sticky. That’s gross.

Jack of Hearts is the story of Jack, a hunter who gave up his heart to the Lady of Twilight to avoid ever feeling the pain of human emotion, and who now serves her as a cold, calculated killer. When he meets Cassandra, a spellbound girl who can only communicate through her mirror image, something awakens in Jack: a distant memory of who he once was. More than this, he begins to realize that his heart might be worth taking back, after all…

Jack of Hearts is out now and available from Amazon and other booksellers.