How Prey Did Not Tackle The Native American Issue, And Why It Doesn’t Matter

There are a few small spoilers in this article, but they are conceptual rather than plot-based.

There are a few small spoilers in this article, but they are conceptual rather than plot-based.

It was around the time I was deleting the third draft for this article when I realised I had absolutely no idea what I was doing and why. Perhaps years of trying to convince people that video games are more than just toys have made me forget that sometimes, video games are just toys. Complicated, expensive toys with lots of blood and tits, but toys nonetheless.

For the record, I was trying to argue that Prey used an alien abduction analogy to explore questions of Native American identity, but I wasn’t even convincing myself.

Prey is not a nuanced exploration of the plight of the Cherokee people in 21st Century America, nor is it an ironic comment on the exploitation of Native American imagery by the same decadent society that made the Native American situation so conflicted in the first place. Prey is a FPS set on an alien spaceship. There are lots of explosions and all the guns look like genitals. It is fun.

Of course, if I had recognised the game for what it was a month ago, I would never have suggested to the GodisaGeek editorial staff that I write an article about it, because it’s really hard to write 1,800 words about how fun it is to blow stuff up and still come out looking like a smartarse. (Gamers like to look like smartarses).

But there I was, less than 24 hours before the deadline, slowly coming to terms with the fact that there simply isn’t anything profound to say about Prey, and the sooner I came to terms with that, the sooner I could finish my article and go to the pub.

Yet I couldn’t help but wonder why was I so convinced that Prey contained some deep message about the Native American situation. I could only conclude that as one of the few Western video games with no white characters (unless you count the barflies in the opening sequence), Prey must be making some kind of point. Although it’s depressing that so few games explore other cultures for sources of inspiration, it shouldn’t matter that Prey does so purely in the interests of making a fun game that looks cool.

The story starts on a Cherokee reservation, where our hero Domasi “Tommy” Tawodi lives with his girlfriend Jen and his grandfather Enisi. Tommy is a frustrated garage mechanic who wants to leave the reservation with Jen and start a new life elsewhere. He tells her (whilst she is trying to work, but never mind) that he thinks of the reservation as “a goddamn cage”, and that the tribe has never meant anything to him.

Despite her miserable job as a barmaid and the lack of prospects on the reservation, Jen is reluctant to leave, saying, “I’m Cherokee, Tommy, just like you. You should be proud of that”.

I suppose it was this brief nod towards the contradiction at the heart of contemporary Native American life that led me down the thorny path to over-analysis. After all, Tommy and Jen’s relationship problems are put on the back burner five minutes later when the bar and everything in it are abducted by a vast alien space ship called the “Sphere” and Tommy has to spend the next eight hours fighting for his life, and Jen’s freedom, with a selection of ever-more preposterous weapons.

It’s not that the Native American thread is dropped completely, just that the sophisticated promise of the opening sequence is replaced with “Spirit Walking”, a gameplay mechanic in which Tommy uses astral projection, shaman-style, in order to circumnavigate obstacles. So that the player doesn’t forget that there’s a Native American thing going on, Spirit Walking is accompanied by some jingly sound effects and a hawk.

There is no message in Prey (at least not one more complex than “stay away from giant sphincters”), and the discussion of Tommy’s Native American heritage exists to flesh out the plot and his character rather than to comment upon the situation of the Native American people. There’s an interesting discussion in the opening sequence between Tommy and his Rent-a-Cherokee grandfather Enisi in which the conflict at the heart of Tommy and Jen’s relationship is exposed:

Enisi: “Jen is Cherokee. She is bound to this land. Asking her to leave is like asking her to give up a part of her soul.”

Tommy: “Doesn’t she want something better than this?”

Enisi: “To be among one’s own people is to truly know where you belong. If there is something better in this life, I have not seen it.”

Tommy: “That’s because you never left.”

Profound, eh?

Although this dilemma is at the heart of Tommy and Jen’s relationship (more on that later), it also provides a handy plot device which enables gameplay and story to complement each other. Although Prey is an FPS in which the protagonist must dispatch with waves of enemies in order to progress through the levels, the gameplay is enriched by the aforementioned “Spirit Walking”.

Just like the Prince’s dagger in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time or Rayman’s detachable fist in, erm, Rayman, “Spirit Walking” is as much a plot device as a gaming mechanic. Tommy’s mastery of the technique reflects his growing acceptance and understanding of the tribal heritage that he so aggressively dismisses in the game’s opening sequence.

And yet we should not confuse this tidy bit of plotting with a wider anthropological concern. Like all good video game super powers, Spirit Walking is linked to Tommy’s character and its power grows with his inner strength, but that’s where its significance ends. To read more into it is not only to waste one’s time, but also overlook the fundamental enjoyability at the heart of Prey.

Native American culture is to Prey what 1980s corporate America is to Die Hard. It provides a solid backdrop to the action and gives the protagonist an identity and a motivation. Without such contexts, both works would still be entertaining (shooting aliens is fun, as is watching a sweaty cop blow stuff up), but they would be unengaging and completely forgettable.

If a video game is to have a plot at all, it generally needs to have a narrative arc that is much the same shape as the difficulty curve. As the game mechanics grow more difficult and complex, so the plot should become more intense. Prey accomplishes this with aplomb, and Tommy’s frantic search for Jen reflects the increasing depth and challenge of the gameplay.

Jen provides Tommy’s motivation throughout. In keeping with his initial characterisation of a man unmoved by community, Tommy never seems especially concerned with the fate of humanity. Although the Sphere and the malevolent “Mother” who controls it are hell-bent on harvesting humanity, Tommy is for the most part preoccupied with saving his girlfriend. This frames the action beautifully because every one of Jen’s plaintive screams serves to remind the player (and, one assumes, Tommy) how passionately she defended her right to stay on her homeland at the beginning of the game. Of course, Jen’s predicament parallels that of humanity as a whole, who have all been ripped from their homeland too.

(i.e. Earth, for those of you struggling with this complex analogy)

Consequently, Tommy and Jen’s domestic disagreement at the beginning of the game succeeds in adding scale to the story. Jen’s aversion to being torn away from her home enhances the sense of horror and injustice the player feels on behalf of all the abducted humans. This feeling is enforced by the glimpses Tommy gains of an ever-receding Earth below the Sphere.

And yet all the responses, awe, fear, rage, empathy, that the game elicits from the player are channelled into making the game fun. Not that the game wouldn’t be fun without them, but that the emotional reaction the player experiences makes the game much more involving. A good thing too, because Prey is so detailed and imaginative that it would be a shame if its stylistic ingenuity was to amount to nothing more than wallpaper, a fate that befalls many a corridor-like FPS.

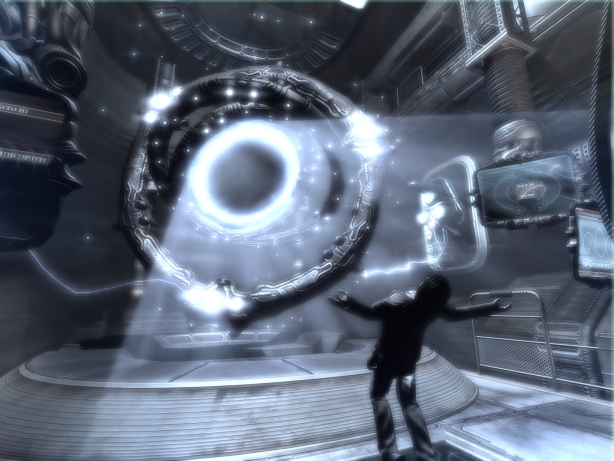

After the whole Native American thing, Prey’s dominant aesthetic is one of lurid bio-mechanical horror. The Sphere is populated by the surviving victims of previous abductions, assimilated into its architecture and evolved beyond recognition. Although Tommy still has to wield the pistol, shotgun and rifle of any FPS protagonist, his guns are living creatures, pulsating hybrids of guts and pistons. As the game progresses, the player learns that evolution is at the heart of the Sphere’s ghastly journey through the galaxy, and is left to imagine the process by which organic creatures become machines, or vice-versa.

In a way, the juxtaposition of visual themes is as intriguing as the plot itself. Because Native American imagery is so rarely touched upon in video games, its richness has all but saturated the player’s consciousness by the time the biomechanical themes start to seep in. The game’s high production values and imaginative use of colour heighten the contrast between the two aesthetics and the overall effect is almost juicy. Add to that the use of portals and the haunting recurrence of “Barracuda” by Heart (first heard in the bar at the very beginning), and the player is continually wrong-footed, unsettled and surprised by what they find around each corner.

Prey was built on Doom 3’s id Tech 4 engine, and it is arguably a much better game. Doom 3 might be a thoroughly competent shooter that stays loyal to its grimy origins, but tramping through its dank corridors is an ultimately predictable journey. Prey, on the other hand, is a grotesquely beautiful exercise in aesthetic innovation.

Because of this, I don’t think it matters that the game never really attempts to explore difficult questions about Native American identity. It tells a fantastic story in an awe-inspiring way using techniques that only video games can use. Although games like Red Dead Redemption are making moves towards a world where video games can discuss difficult historical issues with depth and sensitivity, it shouldn’t matter that games like Prey just want to have fun. If anything we should celebrate their stylistic ingenuity.

If you want to learn more about Native American culture and be entertained at the same time, you might have to read a book. But if you want an example of how an imaginative approach to an old concept can yield rich rewards, look no further than Prey.

Video games are still a young medium. In time, complex stories will be as frequent amongst them as they are now amongst books and films. But we should not let our desire for sophistication cloud our enjoyment of how much fun they can be. Although game designers should never stop striving for greater levels of artistic integrity, they should be equally keen to create games that are exhilerating, spectacular and fun.

In its ingenious melding of Native American imagery with a visceral science-fiction aesthetic, Prey easily manages to be all three.