“Above all, video games are meant to just be one thing: fun for everyone.”

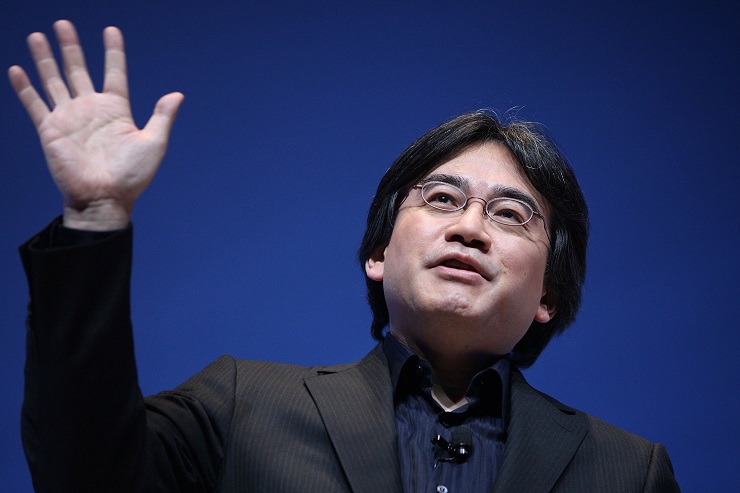

The above quote was said by a man I greatly respect, the late Satoru Iwata. He was a great man, who achieved so much in this industry; many in it are influenced heavily by him, and his work meant so much to many others. The above quote is a nice goal to aim for, but I can’t agree wholeheartedly with this quote, because it’s a pretty narrow minded view of what games are these days, and what they can be; while games are for everyone, they don’t necessarily need to be fun.

For the most part, Nintendo games aren’t known for their sprawling storylines and deep lore (there are exceptions to this, but this is on a broad scale) and as a result, the above quote does mainly hold true to the core values of Nintendo’s output, however, it doesn’t ring true for every company.

As time has gone by, games have changed dramatically. I’ve seen videogames change from monochromatic sprites flickering on a small CRT screen to 100 hour epics, full of life and colour. Video games are not what they used to be. Nowadays we see professional writers such as Rhianna Pratchett and Jesse Stern penning stories for games to add a bit more narrative oomph to our experience. The thing is, as games change and include more complex themes, the criticism of them needs to change too.

It’s possible to look at a game from one angle, and just ask ‘Is it fun: yes or no?’, but that really doesn’t do the majority of titles justice. The Last of Us was a roller coaster of emotions – fear, anger, sadness – but I never felt like I was having fun while I was playing. It was designed to be played in a state of fear – to be made to feel powerless in a hostile world. Horror games like Silent Hill 2 and titles like Journey and ICO are just some of the examples that don’t fit the brief of being just ‘fun’ these days.

We could turn to Bloodborne and the Souls games in this instance. Fun is an incredibly subjective term, something one person finds fun most likely wouldn’t be to someone else’s tastes. Many have a blast playing through From Software’s output, but others really aren’t up to getting their jollies from being pasted into the ground by the same enemy again and again.

Games, like film and books, are looking at communicating a broader range of subjects to those that play them, and they are a fantastic medium to communicate these. Being part of the experience can make the themes that video games explore resonate more with the player. Just recently Adam and myself played through That Dragon, Cancer, and while the game had a sincerely profound effect, I don’t think either of us could truly say that we had fun during our time with it. It’s a very emotional game and every part of it is constructed to inform you as the player what they went through, and how hard it was on them. It aims to communicate how their faith helped them cope. Looking at it as though you were analysing a video game from ‘traditional’ angles would be to its detriment.

Video games are still a fledgling industry and they’ve only been around the mass market since the 1970s; while movies have been around since 1906, books and music even longer, it’s still very much in its infancy. As such, video games as a medium are still growing and changing. Gaming isn’t just solely about fun, it’s now a fully formed entertainment medium, sharing stories and experiences; as such it’s more about engagement than enjoyment.

This is why thinking critical analysis should only focus on ‘fun’ is folly. Reducing video games to that base component results in amazing experiences being left by the wayside due to not being defined as ‘fun’.

Unfortunately, as games critique has wised up to the idea of observing all facets of a game, including the political themes contained therein (see Battlefield Hardline and The Division), the general audience consensus has seen this as a betrayal of what games critique should be. Many voices within the gaming community believe that games critique should look at games like products rather than an entertainment medium, and that we should focus on basics like graphics and fun. This may have been the case in the 90s (remember when games scores were broken down into graphics, sound, gameplay and replayability?), but things have changed drastically since then.

Games and the themes they contain are more complex and as such there needs to be critique to match. Not all critique has to go this way though; if you want to have reviews that concentrate on a base level then seek them out and read them. People shouldn’t be lambasted for wanting to look into the deeper meanings behind what 21st century games and their stories convey.

Everyone is different; criticism – like fun – is subjective, something that resonates with one person will not resonate with another – that’s how individuals work. Should a person find something in a game that they find distasteful to the point it affected how they view the game then it’s up to them to communicate it within their analysis. Everything within a review may not apply to you; but it might to someone else.

Video games have grown up and continue to grow, with games criticism doing the same. It’s about time we understood that.