The news coming out of LucasArts this week, the halt on all internal production and a switch to a model where all Lucas IP is developed externally, is a sad one. It’s not so much the loss of jobs (I’m sure there will be opportunities with other studios for those laid off) or that LucasArts recent track record had been full of hits.

I’m much more selfish than that.

The main cause of sadness was that a piece of my childhood had died. That’s never nice. It’s a reminder that time passes, that things change and that you can’t stop them. It’s like the time at university when I bought a box of Rusks with my meagre weekly shopping budget, insisting they were “delicious when I was a kid”, only to discover that they were drier than a pancake made of hot sand and not delicious at all. The simple Rusk, gone forever and ruined. Time, and Heinz in this case, makes fools of us all.

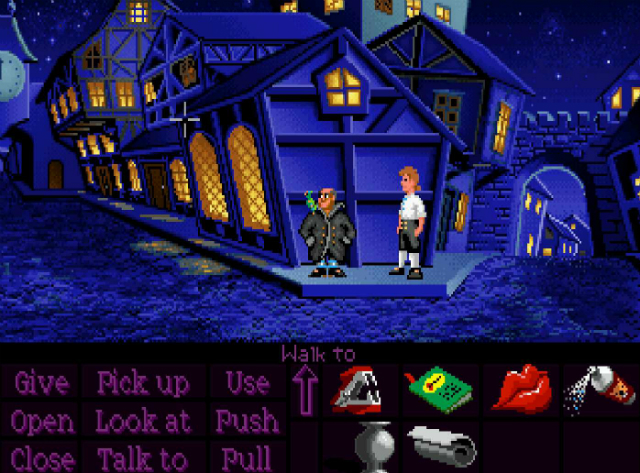

To LucasArts’s credit, it was a far larger part of my childhood than a couple of biscuits could ever be. This is how old I am, but computers were accepted into my childhood house only grudgingly, and games even more so. That all changed with The Secret of Monkey Island. Then Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis and Day of the Tentacle. Those games, those fun and chucklesome stories, changed what my entire family thought games were. They didn’t turn me or my brother into little hermits, rather they became regular weekend and evening fodder for the entire family to puzzle over, laugh about, and share. It was a connected experience in many ways, giving us something else to talk about and a sense of shared accomplishment. Those moments are part of what I want for my family (when I have one); a sense of togetherness from pastimes shared and enjoyed. LucasArts’s games were connecting experiences, at least for me and my family. I’m grateful for being allowed to share them and just as grateful that the guys at LucasArts made them.

This column isn’t a glowing eulogy for LucasArts. There is no objective way to argue that the recent content coming from the Skywalker Ranch has reached anywhere near the heights of the work produced in the early nineties (not that it would be an easy task – early-nineties LucasArts would be on any level-headed commentators list of ‘best developers of the century’). However, there are lessons from those early games that seem to have been all but forgotten in mainstream development.

The most important of those is that, if you design it right, and the story and characters are fun enough, a single player game has the capability to be a multiplayer game. Everyone plays together, sharing the pleasure of a game experience. The Secret of Monkey Island achieved this, as did its sequel. LucasArts haven’t been the only studio to capture this over the past two decades. I’ve mentioned before in this column my intimate knowledge of the world of Final Fantasy VII, though I’ve probably only played the game for a total of three hours. Watching on the sofa as my brother played, chipping in with my fair share of unwanted advice, was actually more enjoyable than playing the game myself. I got to immerse myself in the characters and in the world, and Square repaid me in kind. It should be fairly obvious what Final Fantasy VII and Monkey Island have in common. There are three things, as far as I can see, which link the games (and also happen to be the three things which allow a single player story to be a great shared experience): engaging characters (particularly those that are easy to root for), a quality story and measured pacing.

When you go to the cinema, funny films are always funnier, scary films that bit scarier, and actions films a little more exciting. For me that’s easily explained in two ways; the cinema company has better sound setup than you do and the other people in the cinema create a shared atmosphere, which snowballs out of control. The reason anyone would shell out over £10 to see a film is only because there is “something about” a cinema, and the atmosphere is a huge part of that. Characters like Cloud, like Guybrush and Elaine, are characters that audiences can all identify with. Once a room full of people start rooting for a character the atmosphere that creates, just like at the cinema, is infectious. They can be underdogs or heroes, it isn’t important, what matters is that when someone comes back into the room, after a toilet trip or to top up the crisp bowl, they ask “what’s happened to so-and-so”? Bland and/or faceless characters, like FPS avatars, don’t generally create that same level of rooting interest. How could they? Plotting helps here too, of course. An interesting plot keeps the characters you like moving forward in a direction that holds your attention.

The real key is pacing. When playing CoD there is too little time to speak to anyone next to you (beyond practising some quick fire expletives). Most FPSs are the same way (with games like Bioshock Infinite being an obvious exception). FPSs also have another problem for creating an pleasant shared story environment; camera control. With one player in charge of where everyone is looking it can become disorientating for those just watching. It is an example of a gameplay mechanic dictating not only how a story is experienced, but how many people can comfortably experience it. Both FFVII and Monkey Island use fixed cameras and a steady walking pace and, whilst I’m sure this wasn’t strictly deliberate on the part of the developer, it does make the viewing experience more comfortable for people simply watching, rather than playing. Not just FPSs, but most action games fall foul of similar problems, even if they are supposed to be more deliberate and narrative driven. A recent replaying of Dead Space 2, a game which had a very complicated plot and an array of characters, reminded me of the importance of steady pacing to a shared story experience. That game pushed the player from room to room very quickly and, with so much action, again made it hard to discuss the finer points of the plot (which, if I’m being honest, is too convoluted to ever really warrant someone just watching the game being played). The other problem with action games is that the audience are limited in what they can contribute. When adventuring in Monkey Island, the whole group could solve puzzles. When gunning down terrorists or capping zombies, the role of the non-players is diminished too far.

It seems that with an increasing focus in triple-A on high octane pacing and action, and a huge push towards easily monetised online interactions, the interest in providing a game story that can be shared from the same sofa is dwindling all of the time. That’s an incredible shame. Even Bungie’s Destiny, already being touted for its shared story experiences, isn’t going to encourage families to sit down together and share game narrative in the way that they share films and TV. With rumours of online only consoles abounding, the days of the shared story seem to be drifting into the dim and distant past.

That’s life, though, isn’t it? LucasArts, emblematic to me of sharing time with my family, learning to love games and stories, vanishes just as the style of game they became famous for drifts away with it. It’s a shame, not least because I think there is still a market for it, but also because I feel sorry for the gamers who won’t get to share in the same way that I did.

Still, change brings new and exciting things, and nothing lasts forever. Just ask LucasArts.

——-

Thanks for reading this week’s column. For regular readers, I wanted to let you know that this is it; number twenty is the last one. Writing the column has been a real pleasure over the last year, in no small part thanks to an editing team that let me do my thing with no interference, but mainly due to you, the readers. Thanks to all the commenters, the people who turned up every fortnight and read what I had to say, and to the guy who works in CEX and told Mick that The Story Mechanic was his favourite bit of the site. Makes it all worthwhile. I’ve enjoyed it, I hope you have half as much. See you around.